Transport cafes anywhere else.

We stopped the night in one.

Towns are becoming smaller, fewer and further between.

One of those names from school history or geography that stuck in one's mind.

Until about the 1890 earthquake it was fed from part of the Indus delta.

Now the salt marsh is probably rain fed.

Just right for pelicans.

There's some military around, we are nearing the Pakistan border.

Looks like its ran out of water.

From north east Afghanistan, across Pakistan and north west India.

From about 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE it peaked between 2600 and 1900 BCE.

We put that in the perspective of stonehenge, circa 3100 BCE and the Great Pyramid of Giza (Cheops) about 2650 BCE.

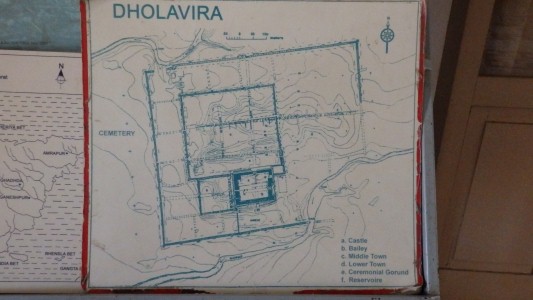

Dholavira was excavated from around 1990.

The Archeological Survey of India was founded in 1861.

The excavation of the first identified site, Harrapa, starting in 1920, was the result of earlier work over many years by the Survey.

The Indus Valley Civilisation was bronze age, around the time of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The weights have a mathematical progression.

Evidence of trade with Mesopotamia has been unearthed.

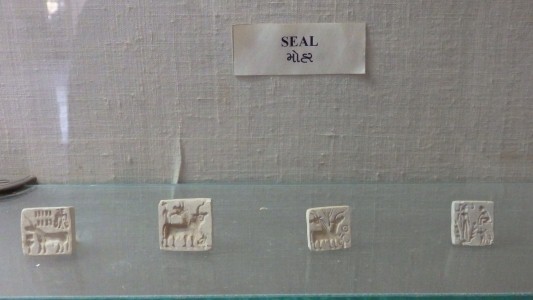

These look like replicas.

Apparently used to seal cargo for trading.

Some with animal designs, some with Indus Valley script.

With lots of steps.

Though there are some suggestions (but not much evidence) there was wheeled transport my guess is it didn't come this way.

The eastern reservoir is in the background.

There is no evidence of palaces or temples. And not much evidence of kings.

Not that they didn't have them, just that huge edifices haven't been found.

Though there must have been social order and organisation to build citadels (there are several in the valley) and trade.

Maybe hierarchical, maybe more republican.

Another is that there is sufficient evidence in the citadel to trace the rise and fall of the Indus Valley Civilisation through several stages.

Though it hasn't really been translated.

No Rosetta Stone.

The sign itself is covered with corugated iron which was a bit difficult to look under for a peek.

The stonework has been lightly dressed.

There's also some suggestion of columns.

Drainage channels lots of ways.

At another of the Harrapan (Indus Valley Civilisation) sites there are many wells, with steps.

One thought is that they are precursors of the ornate Hindu step wells.

The (very minority) necropolis view of this site suggested this may have been a shaft grave! But then we'd wonder what the slab at the far side was for.

Very 'norman' sounding terms to us that don't quite capture the idea of what we are looking at.

Clever people leaned the walls inward.

Probably why they've survived 4-5,000 years.

We aren't sure what the dwellings are being protected from.

Inside the main outer wall.

The bit that looks like rock at the opposite corner to us is unexcavated, compacted, silt.

More a series of reservoirs. Made use of the sandstone bedrock.

The water flow is away from us, towards the west.

We were intrigued by this ramp into the reservoir.

We've seen only two ramps.

Still no evidence of wheels though.

Salt pan in the distance. About 3km away.

We didn't see anywhere they may have been used.

This is a section of terracotta water pipe.

The only piece in the museum.

We took a shortcut.

A good solid wheel with a single iron 'tyre' holding it together.

Well the car park really.

Very friendly, though they do like us eating in their restaurant.

Only Thali. A selection of whatever dishes are available, with lots of chipatis.

Spicy for me. Less so for Ali. It would have been nice if more than the chipatis were warm. Indian waiters seem to enjoy serving chipatis with a flourish, where we would prefer something a little less hands on.

They also forgot to ask us to fill out forms, which was a tad annoying when the immigration service turned up unexpectedly.

The joins in the stonework, part of the eastern reservoir wall, reminded us of other joins we've seen.

This is the east gate to it.

We'd walked through it yesterday without recognising it.

The field is planted with millet. Common in India but the first time we've seen it.

Apparently its grown because it can be planted when it rains then doesn't subsequently need water.

What we see is a very sparse low yield crop.

Raised a bit.

This is the east end of the main (almost single) street.

There are slots, presumably associated with a gate, but not a style we recognise.

Houses here are rectangular.

The small rooms have been labeled bathrooms with drains to the street.

Something about that doesn't quite sound right to us. A lot of building and water carrying effort that hasn't carried over to subsequent culture. Nor was it part of the citadel residences.

But we don't have an alternate explanation.

A short, 50m, street to either side.

In need of traffic control.

Sandstone came from a quarry about 9km away.

There's also limestone used (in the floors of those bathrooms among other places), but we don't know its source.

We didn't make it to the lower town, "where the artisans lived".

In retrospect this is a (almost) round house.

The round houses in the citadel, and presumably this one, are from a later era, as the citadel declined.

Damp at the bottom.

And a very old looking sandstone trough to carry the overflow away.

No evidence of how water is lifted. Maybe now one of the many single cylinder diesel pumps we hear.

We suspect we didn't walk far enough.

There were no photos or description in the museum so we were at a bit of a loss as to what we were searching for.

Easier for the archeologists to speculate with an open book and a clean sheet of paper..

"Don't tread mud into our city!".

No evidence of wheeled traffic and a bit narrow to negotiate if there were.

Lots want their photo taken with us. Some want to talk.

Interesting conversation with family from Delhi. And they had a guide plus spoke excellent English.

One twist. From our culture we look at the walls and wonder who they were protecting the people from. From the Indian culture it was obviously an early statement of the differences in social status that India is well known for.

We settled on the Indian view as there are no ramparts and few weapons found.

Another version is that the walls and height were for flood mitigation. But we haven't found flood gates.

A more obscure version is that the whole site was a necropolis, but we have our doubts about that one.

This is the steps into one of the southern reservoirs.

The circular hole is assumed to be where pots to be filled with water were stood ready.

Thus, lots of design and build effort for collecting water, but not yet ways of lifting it or reticulating it to houses.

By lower social orders!

These are next to the museum.

The remains of circular houses in the citadel are from late in its life, part of the decline.

Next to it are rectangular buildings with thatch roofs.

A fascinating place. We retired to cook Christmas Dinner.